Conference on College Composition and Communication

July 2020

This Ain’t Another Statement! This is a DEMAND for Black Linguistic Justice!

As with previous CCCC/NCTE resolutions and position statements, we situate this demand in our current historical and sociopolitical context. Our current call for Black Linguistic Justice comes in the midst of a pandemic that is disproportionately infecting and killing Black people. We write this statement while witnessing ongoing #BlackLivesMatter protests across the United States in response to the anti-Black racist violence and murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade, and a growing list of Black people at the hands of the state and vigilantes. We are observing calls for abolition and demands to defund the police. We are witnessing institutions and organizations craft statements condemning police brutality and anti-Black racism while ignoring the anti-Black skeletons in their own closets. As language and literacy researchers and educators, we acknowledge that the same anti-Black violence toward Black people in the streets across the United States mirrors the anti-Black violence that is going down in these academic streets (Baker-Bell, Jones Stanbrough, & Everett, 2017). In this current sociopolitical context, we ask: How has Black Lives Mattered in the context of language education? How has Black Lives Mattered in our research, scholarship, teaching, disciplinary discourses, graduate programs, professional organizations, and publications? How have our commitments and activism as a discipline contributed to the political freedom of Black peoples?

It is commonplace for progressive scholars and teachers today to acknowledge students’ multiple language backgrounds. In fact, CCCC/NCTE has created numerous resolutions and position statements related to language variety since the 1974 “Students’ Right to Their Own Language resolution,” a response to the Black Freedom Movements and new research on Black Language of the time. Since then, CCCC/NCTE policymaking in relation to language rights has included the following: Expanding Opportunities: Academic Success for Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students; CCCC Statement on Ebonics; CCCC National Language Policy; CCCC Statement on Second Language Writing and Writers; Resolution on the Student’s Right to Incorporate Heritage and Home Languages in Writing; Supporting Linguistically and Culturally Diverse Learners in English Education; Resolution on Affirming the CCCC “Students’ Right to Their Own Language”; Resolution on Diversity; Resolution on Bilingual Education; Resolution on Developing and Maintaining Fluency in More Than One Language; Resolution on Language Study; Resolution on Inclusion; Resolution on English as the “Official Language”; Resolution on English as a Second Language and Bilingual Education; Resolution on the Responsibility of English Teachers in a Multilingual, Multicultural Society; Resolution on Preparing Effective Teachers for Linguistically Different Students; Resolution on the Students’ Right to Their Own Language.

Though CCCC/NCTE has been active in the ongoing struggle for language rights, Kynard (2013) reminds us that “the possibilities for SRTOL [were] always imagined, and yet never fully achieved [and this] falls squarely in line with our inadequate responses to the anti-systemic nature of the ’60s social justice movements” (p. 74). In reflecting on the current historical moment and movement for Black lives, Baker-Bell (2020) argues that “the way Black language is devalued in schools reflects how Black lives are devalued in the world . . . [and] the anti-Black linguistic racism that is used to diminish Black Language and Black students in classrooms is not separate from the rampant and deliberate anti-Black racism and violence inflicted upon Black people in society” (pp. 2–3). Today, we uphold the updated CCCC statement on Ebonics that explicitly states:

Ebonics reflects the Black experience and conveys Black traditions and socially real truths. Black Languages are crucial to Black identity. Black Language sayings, such as “What goes around comes around,” are crucial to Black ways of being in the world. Black Languages, like Black lives, matter.

As an organization that proclaims “to apply the power of language and literacy to actively pursue justice and equity for all students and educators who serve them,” we cannot claim that Black Lives Matter in our field if Black Language does not matter! We cannot say Black Lives Matter if decades of research on Black Language has not led to widespread systemic change in curricula, pedagogical practices, disciplinary discourses, research, language policies, professional organizations, programs, and institutions within and beyond academia! We cannot say that Black Lives Matter if Black Language is not at the forefront of our work as language educators and researchers! In our efforts to move toward Black Linguistic Justice, we build on the historical resolution/policymaking work within CCCC/NCTE that has laid the foundation for our discipline, but we want to be clear: This Ain’t Another Statement! This is a DEMAND for Black Linguistic Justice! PeriodT!

This list of demands was created by the 2020 CCCC Special Committee on Composing a CCCC Statement on Anti-Black Racism and Black Linguistic Justice, Or, Why We Cain’t Breathe! The members of this committee include April Baker-Bell, Bonnie J. Williams-Farrier, Davena Jackson, Lamar Johnson, Carmen Kynard, and Teaira McMurtry, six Black language scholars whose lived experiences as Black Language speakers inform our teaching, scholarship, research, and activism. Through our collective work on these demands, we are channeling the Black Radicals who came before us, both in our disciplines and in our communities! We intentionally created a fluid text from our multiple voices rather than a singularly voiced, standardized, white document.

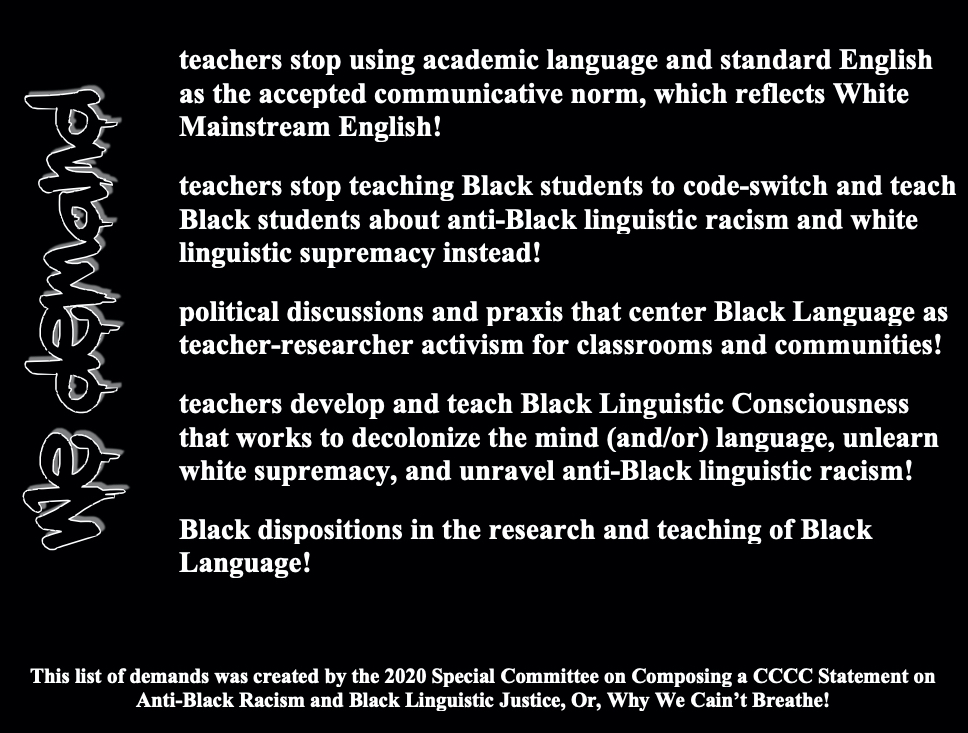

We DEMAND that:

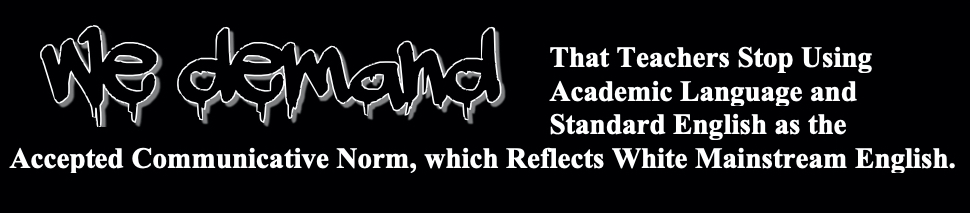

- teachers stop using academic language and standard English as the accepted communicative norm, which reflects White Mainstream English!

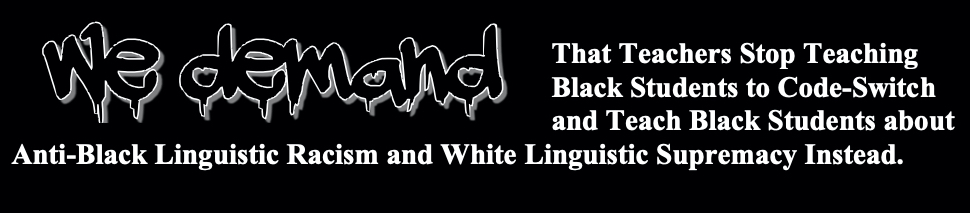

- teachers stop teaching Black students to code-switch! Instead, we must teach Black students about anti-Black linguistic racism and white linguistic supremacy!

- political discussions and praxis center Black Language as teacher-researcher activism for classrooms and communities!

- teachers develop and teach Black Linguistic Consciousness that works to decolonize the mind (and/or) language, unlearn white supremacy, and unravel anti-Black linguistic racism!

- Black dispositions are centered in the research and teaching of Black Language!

We expand on this list of demands in the section below.

DEMAND #1: We Demand that Teachers Stop Using Academic Language and Standard English as the Accepted Communicative Norm, which Reflects White Mainstream English!

The language of Black students has been monitored, dismissed, demonized—and taught from the positioning that using standard English and academic language means success. Since these terms’ early inception, schools have upheld linguistic ideologies that continue to marginalize Black students. Socially constructed terms like academic language and standard English are rooted in white supremacy, whiteness, and anti-Blackness and contribute to anti-Black policies (e.g., English only) that are codified and enacted to privilege white linguistic and cultural norms while deeming Black Language inferior. The learning of standard English has historically been obligatory despite our knowledge that linguistic shaming and dismissal of Black Language has a deleterious effect on Black Language speakers’ humanity (Smitherman, 2006; Rickford & Rickford, 2000). We must acknowledge that Black students’ language education continues to perpetuate anti-Black linguistic racism (Baker-Bell, 2020) and creates a climate of racialized inferiority toward Black Language and Black humanity.

We DEMAND that:

- teachers and researchers acknowledge that socially constructed terms such as academic language and standard English are false and entrenched in notions of white supremacy and whiteness that contribute to anti-Black linguistic racism.

- teachers STOP telling Black students that they have to “learn standard English to be successful because that’s just the way it is in the real world.” No, that’s not just the way it is; that’s anti-Black linguistic racism. Do we use this same fallacious, racist rhetoric with white students? Will using White Mainstream English prevent Black students from being judged and treated unfairly based solely on the color of their skin? Make it make sense.

- teachers reject negative perceptions of Black Language and no longer use racist linguistic ideologies that perpetuate hate, shaming, and the spirit murdering (Johnson et al., 2017) of Black students.

- teachers and researchers reject anti-Black linguistic racism as a way to describe the deficit positioning of Black students’ use of Black Language.

- teachers acknowledge and celebrate Black students’ use of Black Language in all its linguistic and cultural glory.

- teachers and educational researchers champion linguistic justice (Baker-Bell, 2020).

DEMAND #2: We Demand that Teachers Stop Teaching Black Students to Code-Switch! Instead, We Must Teach Black Students about Anti-Black Linguistic Racism and White Linguistic Supremacy!

We DEMAND that language and literacy researchers and educators stop the promotion of code-switching. This approach does not celebrate and love on Blackness and Black Language. In fact, when teachers force Black youth to code their language, it is a form of anti-Black linguistic racism. We DEMAND that language researchers and educators recognize that it is destructive and injurious to ignore the interconnection between language, race, and identity. As Black Language speakers and scholars, we don’t encourage code-switching, because it places whiteness and White Mainstream English on a pedestal while showcasing Blackness and Black Language as inferior, lesser, and secondary. Instead, we encourage, utilize, and elevate the beauty and brilliance in Blackness and Black Language.

We DEMAND that:

- teachers stop policing Black students’ language practices and penalizing them for using it in the classroom.

- teachers stop utilizing eradicationist and respectability pedagogies (Baker-Bell, 2020) that diminish Black students’ language practices.

- Black Language is acknowledged in the curriculum.

- teachers are trained to recognize Black Language and work toward dismantling anti-Black linguistic racism in their curriculum, instruction, and pedagogical practices.

- teachers stop promoting and privileging White Mainstream English, code-switching, and contrastive analysis at the expense of Black students. This is linguistically violent to the humanity and spirit of Black Language speakers.

- teachers recognize that multiple languages can coexist (Young et al., 2014).

DEMAND #3: We Demand that Political Discussions and Praxis Center Black Language as Teacher-Researcher Activism for Classrooms and Communities!

The historical processes of defining and pursuing CCCC/NCTE policies in relation to multilingualism have been vital to classrooms and communities.. However, teacher-researchers must keep pushing further and lay out the specificity of Black Language. Educators who research and support Black Language must move beyond merely understanding and codifying current scholarship, data-driven study, and linguistic analyses. They must be activists. Respect for Black Language fundamentally requires respect for Black lives, a political process that must inherently challenge institutions like schools whose very foundations are built on anti-Black racism. We DEMAND political discussions and praxis of Black Language as guided by the work of teacher-researcher-activists in classrooms and communities who stand against institutions that seek to annihilate Black Language + Black Life.

We DEMAND that:

- researchers, educators, and policymakers stop using problematic, race-neutral umbrella terms like multilingualism, world Englishes, translingualism, linguistic diversity, or any other race-flattened vocabulary when discussing Black Language and thereby Black Lives.

- researchers, educators, influencers, and public scholars reject notions of a single nonmainstream language category that erases the linguistic, cultural, and political specificity of Black Language and Life struggles.

- researchers, educators (in and out of schools), and activists frame Black Language struggles in historical and ongoing Movements for Black Lives.

- ALL WORK related to Black Language and Black youth commit unequivocally to the freedom, dignity, and creativity of young Black people’s lives rather than demand more data extraction and labor from them.

- researchers, scholars, educators, and all everyday Black folx center Black Language on its unique philosophies and survivances of Black Life rather than on a set of linguistic departures from a fictional, white norm.

- researchers, scholars, educators, school/district/national leaders, administrators, and activists address anti-Blackness as endemic to how language functions, how English/education has been historically situated, and how college writing has been actively constructed.

DEMAND #4: We Demand Black Linguistic Consciousness!

We DEMAND the cultivation of Black Linguistic Consciousness. Raising Black Linguistic Consciousness requires place and space for divulging untold truths. This, in turn, prioritizes the reversing of anti-Black linguistic racism, the healing of the souls of Black folks, and the empowering of agentive political choices that call for the intentional employment of Black Language (Baker-Bell 2020; Kynard, 2007; Richardson, 2004). This is the exercising of liberation. Further, this requires that all students get an opportunity to learn about Black Language from Black language scholars or experts (via texts, lectures, etc.). For Black students specifically, it is imperative that they learn Black Language through Black Language; that is, they learn the rich roots and rhetorical rules of Black Language (Baker-Bell, 2020) by any means necessary. At the same time, this warrants the ceasing of anti-Blackness and miseducation—specifically, ineffectual language arts instruction—that misguidedly limits language mastery to White Mainstream English (revisit Demand #1). Black students need the kind of artful language instruction in which they are positioned as the linguistic mavens they are who can teach you a thing or two about language.

We DEMAND that:

- teachers and researchers decolonize their minds (and/or) language of white supremacy and anti-Black linguistic racism and study the origin theories and sociolinguistic principles that exist about Black Language.

- teachers engage their students in “Black linguistic consciousness-raising that provides them with the critical literacies and competencies to name, investigate, and dismantle white linguistic hegemony and anti-Black linguistic racism” (Baker-Bell, 2020, p. 86).

- teachers reject deficit descriptions and other misnomers (e.g., home language, informal English, improper speech, etc.) that disrespects the existence and essence of Black Language. Call it what it is: Black Language!

- teachers, researchers, and scholars put some respeck on Black Language and refrain from engaging in Black linguistic appropriation (Baker-Bell, 2020). This means that you stop the hypocrisy. Realize that it is not okay for Black Language to be used by nonnative users for popular and capital gain while native users are simultaneously mocked and widely denigrated.

- teachers not dismiss Black Language simply as a dialect of English, and do not treat it as a static anachronism—it’s not a thing of the past, spoken only by Black people who are positioned in a “low” or “working class.” Recognize it as a language in its own right! Revisit Demand #1 again.

- teachers respeck Black thought and how that thought manifests in Black speech and writing. That is, it might not sound like you desire it to, but remember, it sounds real right, regardless of unrelenting white supremacist socialization.

DEMAND #5: We Demand that Black Dispositions Are Centered in the Research and Teaching of Black Language.

We DEMAND that research and the teaching of Black Language center the work of Black language scholars whose research agendas and expertise are informed by their lived experiences as Black people and Black Language speakers. We specifically call for the centering of scholarship by Black women and early career Black language scholars whose scholarship is often marginalized in the research literature. We denounce the centering of research by white scholars on Black Language, which has too often been elevated in the field and deemed leading and foundational scholarship (e.g., Caldwell, Labov, Wolfram, Heath, etc.). This has contributed to many white and non-Black scholars of color gaining a platform to discuss Black Language and culture without including Black perspectives or commitments to the political freedom of Black peoples. This is an act of dehumanization and erasure of Black bodies from our own lived experiences! We demand that researchers, teachers, editors, and those in positions of leadership within CCCC/NCTE (and all professional organizations) call out these examples of anti-Black violence as well as hold themselves accountable.

We DEMAND that:

- teachers assign readings that are written by foundational and contemporary Black language scholars.

- teachers include assignments that give Black students the option to explore or connect with their cultural knowledge and perspectives.

- professional organizations whose popularity hinges on Black language scholars’ presentations and service learn to center them and not the white scholars who merely tokenize such work.

- research submitted for publication on Black Language and culture be reviewed by Black language scholars whose research agenda and expertise are informed by their lived experiences as Black people and Black Language speakers.

- the review process for CCCC/NCTE journals (and all educational scholarship) include criteria that reflect a Black-centered citation politic. When evaluating manuscripts on Black Language and culture, authors must include citations that center the scholarship of Black scholars whose research agenda is informed by their lived experiences as Black people and Black Language speakers.

- graduate programs in the fields of composition studies and English education develop the next generation of researchers’ Black Linguistic Consciousness of citationality politics and a Black activist research disposition.

CODA

If reading this made you feel some kinda way, instead of coming for these demands, let us help you redirect that energy. If you thought these demands were simply about teaching within traditional white norms or fixing Black students and their language practices, you got it wrong! This is a DEMAND for you to do much better in your own self-work that must challenge the multiple institutional structures of anti-Black racism you have used to shape language politics. To all the upper-level college administrators, mid-level college managers, WPAs, deans, department chairs, superintendents, school district leaders, principals, school leaders, curriculum coordinators, state and national policymakers, and editors: We see y’all! Don’t get it twisted—these demands are for y’all too!

Don’t get silent when it comes to Black Lives and Black Language in these academic streets! Keep that same energy when it comes to fighting for Black Lives in our field that you had when you used the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter on your social media platforms following George Floyd’s murder; chanted #SayHerName for Breonna Taylor and #AllBlackLivesMatter for Tony McDade at your first #BLM protest this summer; sent that email/text to your Black “friend” to profess your allyship; and helped craft that Black Lives Matter statement on behalf of your institution or department.

We DEMAND Black Linguistic Justice! And in case you’ve forgotten what WE mean when WE say Black Lives Matter, we stand with the words of the three radical Black organizers and freedom dreamers/fighters—Alicia Garza, Patrisse Khan-Cullors, and Opal Tometi—who created the historic political project #BlackLivesMatter:

Black Lives Matter is an ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise. It is an affirmation of Black folks’ humanity, our contributions to this society, and our resilience in the face of deadly oppression.

This list of demands was generously created by the 2020 CCCC Special Committee on Composing a CCCC Statement on Anti-Black Racism and Black Linguistic Justice, Or, Why We Cain’t Breathe! The members of this committee include:

April Baker-Bell, Chair, Michigan State University

Bonnie J. Williams-Farrier, California State University (Fullerton)

Davena Jackson, Boston University

Lamar Johnson, Michigan State University

Carmen Kynard, Texas Christian University

Teaira McMurtry, University of Alabama at Birmingham

REFERENCES

Baker-Bell, A. (2020). Linguistic justice: Black language, literacy, identity, and pedagogy. Routledge & National Council of Teachers of English.

Baker-Bell, A., Jones Stanbrough, R. J., & Everett, S. (2017). The stories they tell: Mainstream media, pedagogies of healing, and critical media literacy. English Education, 49(2), 130–52.

Johnson, L. L., Jackson, J., Stovall, D. O., & Baszile, D. T. (2017). “Loving Blackness to death”: (Re)Imagining ELA classrooms in a time of racial chaos. English Journal, 106(4), 60–66.

Kynard, C. (2007). “I want to be African”: In search of a Black radical tradition/African-American-vernacularized paradigm for “Students’ right to their own language,” critical literacy, and “class politics.” College English, 69(4), 360–90.

Kynard, C. (2013). Vernacular insurrections: Race, Black protest, and the new century in composition-literacies studies. SUNY Press.

Richardson, E. (2004). Coming from the heart: African American students, literacy stories, and rhetorical education. In E. B. Richardson & R. L. Jackson II (Eds.), African American rhetoric(s): Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 155–69). Southern Illinois University Press.

Rickford, J. R., & Rickford, R. J. (2000). Spoken soul: The story of Black English. Wiley.

Smitherman, G. (2006). Word from the mother: Language and African Americans. Routledge.

Young, V. A., Barrett, R., Young-Rivera, Y., & Lovejoy, K. B. (2014). Other people’s English: Code-meshing, code-switching, and African American literacy. Teachers College Press.

This position statement may be printed, copied, and disseminated without permission from NCTE.

Cassandra Woody is an assistant teaching professor in the First-Year Composition Department at the University of Oklahoma, where she coauthored the first-year composition curriculum. Her research interests include feminist rhetorics, feminist writing program administration, rhetorical theory, and composition studies. Her area of focus is currently housed within first-year composition. As a researcher and teacher, she is concerned with the way rhetorics and the teaching of them may move students to recognize power, privilege, and the fluidity of one’s subject position within rhetorical negotiations.

Cassandra Woody is an assistant teaching professor in the First-Year Composition Department at the University of Oklahoma, where she coauthored the first-year composition curriculum. Her research interests include feminist rhetorics, feminist writing program administration, rhetorical theory, and composition studies. Her area of focus is currently housed within first-year composition. As a researcher and teacher, she is concerned with the way rhetorics and the teaching of them may move students to recognize power, privilege, and the fluidity of one’s subject position within rhetorical negotiations. Scott Wible is an associate professor in the English Department, director of the Professional Writing Program, and a faculty fellow in the Academy for Innovation & Entrepreneurship at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Scott Wible is an associate professor in the English Department, director of the Professional Writing Program, and a faculty fellow in the Academy for Innovation & Entrepreneurship at the University of Maryland, College Park. Dana Lynn Driscoll is a professor of English at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, where she directs the Kathleen Jones White Writing Center and teaches in the Composition and Applied Linguistics doctoral program. She currently serves as coeditor for the open-source first-year writing textbook series Writing Spaces, which offers free readings and instructional materials for composition courses. She has published widely on writing transfer, learning theory, writing centers, and research methods and has offered plenary addresses and workshops around the globe. Her coauthored 2012 article with Sherry Wynn Perdue won the IWCA’s Outstanding Article Award.

Dana Lynn Driscoll is a professor of English at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, where she directs the Kathleen Jones White Writing Center and teaches in the Composition and Applied Linguistics doctoral program. She currently serves as coeditor for the open-source first-year writing textbook series Writing Spaces, which offers free readings and instructional materials for composition courses. She has published widely on writing transfer, learning theory, writing centers, and research methods and has offered plenary addresses and workshops around the globe. Her coauthored 2012 article with Sherry Wynn Perdue won the IWCA’s Outstanding Article Award. S. Rebecca Leigh is a professor in the Department of Reading and Language Arts at Oakland University in Rochester, MI. Her research interests include multiple ways of knowing, writing, teacher, and doctoral education. Her current research focuses on how access to art serves as a pathway to literacy learning and its impact on students as writers. Her work has appeared in Language Arts, English Journal, and Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. Leigh can be reached at

S. Rebecca Leigh is a professor in the Department of Reading and Language Arts at Oakland University in Rochester, MI. Her research interests include multiple ways of knowing, writing, teacher, and doctoral education. Her current research focuses on how access to art serves as a pathway to literacy learning and its impact on students as writers. Her work has appeared in Language Arts, English Journal, and Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. Leigh can be reached at  Nadia Francine Zamin is an assistant professor of the practice at Fairfield University. Her academic work centers around supporting faculty teaching writing across the curriculum, mindfulness interventions in composition, and writing program assessment, while her research is concerned with the cultures surrounding learning and on the creation of healthy and sustainable learning and composing environments for student and faculty writers. Her work has also appeared in Across the Disciplines.

Nadia Francine Zamin is an assistant professor of the practice at Fairfield University. Her academic work centers around supporting faculty teaching writing across the curriculum, mindfulness interventions in composition, and writing program assessment, while her research is concerned with the cultures surrounding learning and on the creation of healthy and sustainable learning and composing environments for student and faculty writers. Her work has also appeared in Across the Disciplines. Antonio Byrd is an assistant professor of English at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. He teaches Black/African American literacy histories, digital rhetoric, multimodal composition, and professional and technical writing. Byrd researches how Black/African American adults learn and use computer programming to address racist policies and create sustainable futures for their communities. His work has appeared in Literacy in Composition Studies.

Antonio Byrd is an assistant professor of English at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. He teaches Black/African American literacy histories, digital rhetoric, multimodal composition, and professional and technical writing. Byrd researches how Black/African American adults learn and use computer programming to address racist policies and create sustainable futures for their communities. His work has appeared in Literacy in Composition Studies.