We Are All Writing Teachers*: Returning to a Common Place

2021 CCCC Annual Convention

April 7–10, 2021

Spokane, Washington

Program Chair: Holly Hassel, North Dakota State University, in collaboration with Julie Lindquist, Michigan State University (CCCC 2020 Program Chair)

See Holly’s blog post, CCCC 2021 Decisions and Advice, for recommendations for proposers who are resubmitting or revising accepted (or unaccepted) proposals from the 2020 Convention.

Submit a Proposal for the 2021 CCCC Convention

Call for Proposals

The mission of CCCC includes the following goals:

- sponsor and conduct research that produces knowledge about language, literacy, communication, rhetoric, and the teaching, assessment, and technologies of writing;

- create collaborative spaces (such as conferences, publications, and online spaces) that enable the production and exchange of research, knowledge, and pedagogical practices;

- develop evidence- and practice-based resources for those invested in language, literacy, communication, rhetoric, and writing at the postsecondary level;

- advocate for students, teachers, programs, and policies that support ethical and effective teaching and learning.

Our annual gathering regularly seeks to work toward these goals for research, collaboration, and knowledge sharing. The 2020 CCCC Convention in Milwaukee faced an unprecedented challenge, and to meet the responsibilities we have to our communities in the face of what the World Health Organization named a global pandemic, our annual opportunity to gather, converse, and collaborate looked much different in 2020. To move the work of Milwaukee forward, I invite us to link Julie Lindquist’s call to consider commonplaces with these stated goals of the organization, as well as the role, value, and work of teaching in the field.

In her CCCC 2020 CFP for Milwaukee, Lindquist invited us to inquire into the terms of inclusivity by considering how our field is governed and organized by what Aristotle described as topoi, or commonplaces, or “a store of common understandings, a set of shared cultural resources, by means of which rhetoricians could construct arguments.” She asked us to reflect, as well, on how commonplaces would come to signify “ideological means for exclusion from the most exclusive and privileged scenes of knowledge production” as well as on how “If the commonplaces of a given community (or culture) give us a way to understand what it believes and values, then they are also a way for us to see how it defines and defends its borders.”

This year, the theme for the convention tackles what both Julie and I view as one of our most contested sets of commonplaces—common understandings of our roles as teachers and scholars. Though the field of composition and rhetoric (or writing studies, a somewhat more expansive term) has been called by Joseph Harris a “teaching subject,” the conditions in which we work vary greatly, and the cultural value of teaching in the field is not matched by the material value provided.

I hope to focus this year’s convention on practice—practice that is theoretically situated, evidence based, and research informed, but practice nonetheless. It has been twenty years since our convention focused explicitly on teaching (1999, Atlanta: “Visible Students, Visible Teachers”), and as a two-year college teacher-scholar whose career has focused on systematic inquiry into the teaching and learning of college composition, I’m especially drawn to returning this year in Spokane to the work of our teaching, particularly in first-year writing and other transitional moments in our college classrooms.

More than ever before, we have been called upon to explore new possibilities for teaching and learning in remote, synchronous, and asynchronous ways. I invite you to submit proposals that address the following dimensions of the field of writing studies, all while critically engaging with one of the key commonplaces that Lindquist called to our attention in 2020: dynamic questions that “entail ideas about learners and learning—what learners do and need, how learning happens, and on what grounds learning may be refused.”

WE: CCCC and the convention it sponsors serve diverse audiences. One of the preoccupying questions of the field is who we are. Composition Studies? Rhetoric? Rhetoric and Composition? Writing Studies? Communication studies, rhetoric studies, and other adjacent fields also have found a place at the convention. Disciplinarity has remained an intense focus since foundational works like Stephen North’s The Making of Knowledge in Composition: Portrait of an Emerging Field (1987) and in recent works like Composition, Rhetoric, and Disciplinarity (Malenczyk, Miller-Cochran, Wardle, and Yancey, 2018). Decolonizing Rhetoric and Composition Studies: New Latinx Keywords for Theory and Pedagogy (Ruiz and Sánchez, 2016) and many others have interrogated dominant rhetorical traditions. The question of who belongs and who is excluded from the work of writing studies suffuses our scholarly conversations, even as some teachers of writing continue to document how the field does not reflect their needs (Larson, 2019).

ARE: Our profession and discipline occupy diverse spaces: traditional liberal arts colleges, community and technical colleges, online, hybrid, tribal colleges, HBCUs, HSIs, Research 1 institutions, STEM campuses, and high school dual-enrollment classrooms. We teach through interactive video, in community centers, in writing centers, in prisons, and across the curriculum and across campus units. We teach first-year students in credit-bearing courses and in courses that help students transition to postsecondary literacy, including nondegree credit and basic writing courses, integrated reading and writing, first-year seminars, and corequisite support courses (Stretch, Studio, ALP). We teach creative writing, technical writing, writing-intensive literary studies courses, upper-division, and discipline-specific courses. We continue to teach writers to enter into our scholarly conversations and disciplinary conversations throughout graduate education. We conference, freewrite, use models, and use workshopping and peer review. We use assessment to inform instruction. We ask students to journal, to document their reading difficulties and insights, to address learning outcomes, to build relationships with their instructors and with each other. We read and analyze texts, and we engage with communities inside the classroom, on campus, and beyond. We respond to real and imagined audiences.

ALL: The question of who teaches writing, what counts as scholarly expertise, and who is or is not invited to see themselves as a member of the profession is a pressing issue in the field. Writing teachers are students in masters’ programs in English, doctoral students, contingent faculty (from a range of employment positionalities—full-time lecturers with benefits; those on a semester-by-semester contact; those with rolling horizon contracts), full-time faculty, those on the tenure track, tenured, high school teachers credentialed by college programs; faculty from a wide range of disciplines teaching first-year seminars; faculty working across the curriculum infuse their disciplinary courses with writing instruction and writing activities. Is there any single uniting identity that speaks to the work that writing studies does and what constitutes participation in its knowledge making (Penrose, 2012)? And what opportunities for institutional and collegial collaboration might make the field more inclusive, more connected?

WRITING: What are we teaching when we say we teach writing? As instructors and as a profession, we use the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing, the WPA Outcomes for FYW, or textbooks on genre, writing about writing, threshold concepts, and digital composing. We use theories from rhetorical, critical, composition, feminist, antiracist writing, and practitioner/kitchen table theories. We are decolonizing our syllabi and seeking authentic audiences for our students and their ideas. We use the position statements, resources, and documents from NCTE, CCCC, TYCA, CWPA, RSA, NCA, and many other professional organizations. Likewise, critical attention to what “writing” means in the 21st century continues to animate our field (Inoue, 2019; Kareem, 2019; Wyatt and DeVoss, 2017; Young, 2004 and 2013) and press us to consider what communication, composing, and writing instruction look like in the immediate and more distant future. If we teach visual rhetoric, communication, speaking, digital media, or other fields emerging from and adjacent to writing studies, do we still teach “writing”?

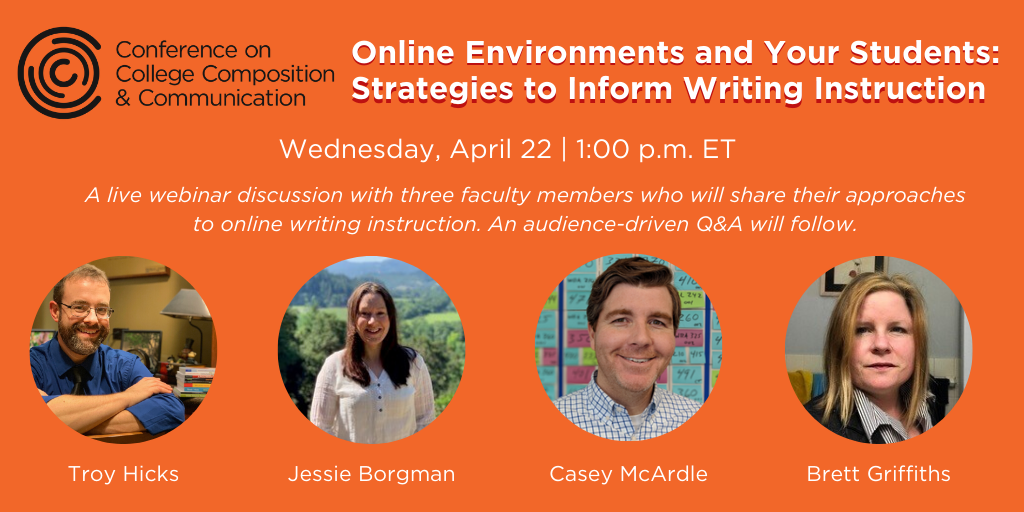

TEACHERS: Some members of CCCC and academics working in related fields see a clear division between their responsibilities as teacher or scholar; others identify as primarily one or the other. My own identity has—through my entire career—rested primarily on my role as a teacher, even as I have engaged in the work of contributing to professional conversations through publication, research, and service. At this year’s convention, I invite proposers to consider how their teaching and teacherly identity are constituted. Regardless of whether you hold a primarily teaching-intensive or primarily research-intensive appointment, what value do you attach to teaching, advising, mentoring? How do you make space for it in your work? And how do we (or do we not) value it in the profession, from the first year of college to graduate education? Leonard Cassuto and Elaine Maimon have both called for renewed and intense attention within the field of English studies to the quality of teaching at the foundation of college writing and in graduate programs. Patrick Sullivan has asked two-year college instructors to consider themselves “teacher-scholar-activists,” while Brett Griffiths calls for “autonomous teacher advocates” who take an “assertive and visible role in . . . explicitly shaping learning outcomes in their departments and communicating them to others” (60). This call for assertiveness and visibility also compels me to continually ask who and what we are “disciplining” when we are engaged in field-building—and how we are participating not just in school but schooling. Are our teacherly practices supporting growth—or compliance? Are our students learning, or being schooled (Warner, 2019)?

AND YET*. . . As Linda Adler-Kassner has written, “writing is never just writing,” and so we know that even as we are all writing teachers, we teach, learn, write, and research from different places and positions. We work within colonized institutions and places; we work within an academic hierarchy in which teaching and research are becoming increasingly separate activities, with a smaller class of writers and researchers allowed time and labor to contribute to knowledge and rapidly growing class of faculty with limited time to devote to ideas, research, scholarship, and inquiry. Some of us work as apprentices as graduate workers; others work on semester-to-semester contracts, with limited access to resources typically afforded to college faculty. Some of us rarely interact with first-year students; others work exclusively with students who are just encountering college literacies and learning. Some of us teach writing within extremely constrained circumstances; some writing teachers operate from a place of complete autonomy. Some of us, in WPA roles, set the agenda and curriculum for others; some teach from the agenda of those in charge.

And more, does the field’s body of knowledge about teaching and learning reflect these diverse spaces, places, and people? Are we deploying empirical methodologies to understand our classrooms across program types? Are we sufficiently inviting students into our inquiries as co-researchers? Are we using methods of systematic inquiry (Hassel, 2013) that will build foundations for informing program development, praxis, and professional knowledge?

Our programs, students, and positions are diverse, and the texture of our work and day-to-day realities are similarly diverse. It is my hope that CCCC 2021 in Spokane centers the disciplinary conversation on the work of the teaching of writing, and our diverse positions and practices.

At CCCC 2021 in Spokane, you’ll see a convention where new features or changes respond directly to the feedback from CCCC members, while others bring forward the exciting opportunities for engagement that could not be replicated by an online version of CCCC:

- Stage 1 Review: There is an open invitation for CCCC Stage 1 reviewers this year. Many CCCC members express a lack of clarity about how to get involved in the process of building the program. Please indicate your willingness to participate as a Stage 1 reviewer on this form by Friday, May 8, 2020. This decision responds to multiple reports from CCCC constituent groups.

- Availability of Proposal Feedback: The CCCC Committee on the Status of Graduate Students (what is called in the CCCC constitution a “special committee”—or a committee formed for a period of 3 years to achieve a specific goal or purpose) conducted a survey of graduate students presented in this report. In response, the reviewer comments and feedback from the Stage 1 proposal review will be made available to submitters following the review process.

- Special Interest Groups: Historically, the Special Interest Groups have been held concurrently in two evening slots on Thursdays and Fridays. There has long been member interest in having these dispersed throughout the program so that attendees can connect with others in an interactive setting, across multiple professional and personal interests. In 2021, SIGs will be held during the regular convention program day in addition to the four evening slots, leaving evenings freer for program participants and allowing attendees to attend multiple SIGs as part of their convention schedule. This decision responds to questions asked during the 2019 business meeting and the postconvention survey on member engagement which asked conventiongoers about their most significant convention experience. Over and over again, a theme identified was the opportunity to engage in small, interactive group settings with peers who share personal and professional interests and identities.

- All-Convention Conversation: The Thursday convention plenary has been reserved for awards and the Chair’s address. Spokane 2021 will feature a second plenary on Friday morning that offers attendees the opportunity to engage deeply in discussions about the future of the organization. The session will be led by the CCCC Committee for Change, which has been charged (2019–2022) by past CCCC Chair Asao B. Inoue with reviewing and addressing the CCCC governance documents—the constitution and bylaws—to increase transparency and inclusion in the organization.

- Changes to the Clusters: Most of the clusters to which you can identify and categorize your proposals remain the same. There are a few new additions and adjustments:

- Access: This year’s special cluster makes space for presentations, workshops, or sessions that address the topic of “access.” I define this broadly, both in the sense of making our classrooms, practices, and research available to all, and in the sense of making college accessible to the full range of students who are pursuing postsecondary education.

- Reading: Though reading remains a kind of implicit dimension of writing instruction, this cluster designation aims to encourage proposals that focus on the role of reading in writing courses, whether that is critical reading, Integrated Reading and Writing Courses (IRW), writing about reading, or other sessions that will help us as a discipline to consider the interconnected nature of reading and writing practices.

- Labor: Though labor can be broadly defined, I think here of the very specific definition of labor as our working conditions and draw inspiration from concerns, strategies, and goals of the Labor Movement. This cluster dedicates a space for the material conditions of writing instruction and the influence of labor conditions on teaching and learning conditions.

In addition, to continue the work that was put on hold from Milwaukee 2020, several features of the 2020 program will be part of the 2021 program:

- Documentarians: To launch the work that would have taken place in Milwaukee, the Spokane convention will include the Documentarian role, led by Julie Lindquist and her team at MSU. As Julie wrote in 2020:

A commonplace about program participation is that in order to be listed as a contributor to the convention program, you must have a role in a scheduled session. In 2020, a new “speaking” role will be introduced: the Documentarian. The CCCC Documentarian role is an opportunity for attendees to participate in a new way, and to take part in a collaborative inquiry into what a conference is and does—and for whom—and to teach the rest of us. The Documentarian role has been designed to respond to four primary questions about how attendees experience the CCCC Annual Convention:

What does it mean to attend the convention? The efforts of Documentarians will help the CCCC community better understand the range of attendees’ convention experiences.

What do we learn at the convention? The Documentarian role is designed not only to document things that happen at the convention, and the perspectives of those who experience those things, but to help Documentarians—and those who may benefit from their stories—identify the learning they did by way of their convention experiences.

What are the outcomes of a convention experience? The results of the Documentarians’ efforts will be made available to the CCCC community in a variety of ways, including both formal and informal publication of the resulting documentary stories.

What does it mean to be included? How diverse are our experiences? The Documentarian role is meant to provide a new form of convention access to a broad range of attendees. Because they fill a “speaking” role (technically, a speaking back role), Documentarians will appear on the program.

Documentarian roles are available to those with or without another speaking role at CCCC. For example, it is possible to be on the program solely as a Documentarian or as a panelist and a Documentarian. Documentarians’ products will be realized as a variety of written (i.e., alphabetic—not filmed or audio-recorded) products that capture highlights of, and reflections on, Documentarians’ convention experiences.

What will YOU do should you serve as a Documentarian? As a Documentarian, you’ll complete a brief instructional module, attend the convention, choose a path through the convention experience, record some observations about the things you see and hear, and then compose a reflective narrative about your experiences. To help you along in this work, you’ll be given a prompt and a set of guidelines for planning, attending, documenting, and reflecting on your experience with the convention. You’ll also be encouraged to meet and connect with other Documentarians throughout the convention in any spaces made available for this purpose. You can indicate your interest in serving in a Documentarian role as part of the regular review process.

- Engaged Learning Experience Sessions: Julie Lindquist’s 2020 CFP introduced “Engaged Learning Experience” sessions, an alternative genre of concurrent session, a dedicated space for invention, problem-solving, and experiential learning. We encourage those who proposed ELEs for 2020 to submit proposals for these sessions to the 2021 convention. As with all sessions, leaders should think in terms of a learning goal and a means for moving participants toward it. In the case of Engaged Learning Experience sessions, some means for moving toward learning goals might include things like problem-solving groups, spoken-word poetry, dramatization/improv, making, role-playing, storytelling.

- Think Mobs: As a discipline, we share certain commonplaces of knowledge and practice—but, as we all know, local institutions have their own commonplaces of intellectual and practical activity. To open opportunities for further conversations about commonplaces of work, practice, and professional life, Julie Lindquist and her team will arrange pop-up discussion groups in locations on- and off-site. Details from the Local Arrangements Committee website will offer more information about times and places.

For questions about the convention, contact Convention Chair Holly Hassel or Convention Assistant Andrea Stevenson. For questions about Documentarian roles, Think Mobs, or Common Grounds, contact Julie Lindquist. For questions about Spokane and the work of the Local Arrangements Committee, contact Bradley Bleck. Other questions? Contact us.

Review Criteria

Each proposal will be evaluated regarding how well it

- addresses teaching and learning in postsecondary writing;

- is situated within relevant scholarship or research in the field;

- reflects an awareness of audience needs relevant to the topic;

- demonstrates a clear and specific plan that aligns with the criteria for the selected session type.

Program Clusters

| 2018

1. Pedagogy (#Pedagogy)

2. Basic Writing (#BW)

3. Assessment (#Assess)

4. Rhetoric (#Rhetoric)

5. History (#History)

6. Technology (#Tech)

7. Language (#Language)

8. Professional Technical Writing (#PTW)

9. Writing Program Administration (#WPA)

10. Theory (#Theory)

11. Public, Civic, and Community Writing (#Community)

12. Creative Writing (#Creativewriting) |

2019

1. First-Year and Advanced Composition

2. Basic Writing

3. Community, Civic & Public

4. Creative Writing

5. History

6. Information Technologies

7. Institutional and Professional

8. Language

9. Professional and Technical Writing

10. Research

11. Writing Pedagogies and Processes

12. Theory

13. Writing Programs |

2020

1. First-Year and Basic Writing

2. Writing Programs and Majors

3. Approaches to Learning and Learners

4. Community, Civic, and Public Contexts of Writing

5. Creative Writing and Publishing

6. History

7. Information Technologies and Digital Cultures

8. Institutions, Labor Issues, and Professional Life

9. Language and Literacy

10. Professional and Technical Writing

11. Research

12. Theory and Culture

13. Inventions, Innovations, and New Inclusions |

2021

1. First-Year Writing

2. College Writing Transitions

3. Labor

4. Writing Programs

5. Community, Civic, and Public Contexts of Writing

6. Reading

7. Access

8. Historical Perspectives

9. Creating Writing and Publishing

10. Information Literacy and Technology

11. Language and Literacy

12. Professional and Technical Writing

13. Theory and Research Methodologies |

Works Cited

Adler-Kassner, Linda. “2017 Chair’s Address: Because Writing Is Never Just Writing.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 69, no. 2, 2017, pp. 317–340.

Cassuto, Leonard. The Graduate School Mess: What Caused It and How We Can Fix It. Harvard UP, 2015.

Griffiths, Brett. “Professional Autonomy and Teacher-Scholar-Activists in Two-Year Colleges: Preparing New Faculty to Think Institutionally.” Teaching English in the Two-Year College, vol. 45, no. 1, 2017, pp. 47–68.

Hassel, Holly. “Research Gaps in Teaching English in the Two-Year College.” Teaching English in the Two-Year College, vol 40, no. 4, 2013, pp. 343–363.

Inoue, Asao. “How Do We Language So People Stop Killing Each Other, or, What Do We Do about White Language Supremacy?” Keynote Address. Conference on College Composition and Communication. March 14, 2019.

Kareem, Jamila. “A Critical Race Analysis of Transition-Level Writing Curriculum to Support the Racially Diverse Two-Year College.” Teaching English in the Two-Year College, vol. 46, no 4, 2019, pp. 271–296.

Larson, Holly. “Epistemic Authority in Composition Studies: Tenuous Relationship between Two-Year English Faculty and Knowledge Production.” Teaching English in the Two-Year College, vol. 46, no. 2, 2018, pp. 109–136.

Maimon, Elaine. Leading Academic Change: Vision, Strategy, Transformation. Stylus, 2018.

North, Stephen. The Making of Knowledge in Composition: Portrait of an Emerging Field. Heinemann, 1987.

Penrose, Ann. “Professional Identity in a Contingent-Labor Profession: Expertise, Autonomy, Community in Composition Teaching.” WPA, vol. 35, no. 2, 2012, pp. 108–126.

Ruiz, Iris, and Raúl Sánchez. Decolonizing Rhetoric and Composition Studies: New Latinx Keywords for Theory and Pedagogy. Palgrave-McMillan, 2016.

Sullivan, Patrick. “The Two-Year College Teacher-Scholar-Activist.” Teaching English in the Two-Year College, vol. 42, no. 4, 2015, pp. 327–350.

Warner, John. Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities. Johns Hopkins UP, 2019.

Wyatt, Christopher Scott, and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss, eds. Type Matters: The Rhetoricity of Letterforms. Parlor Press, 2017.

Young, Vershawn Ashanti. “Keep Code Meshing.” Literacy as Translingual Practice: Between Communities and Classrooms, edited by Suresh Canagarajah, Routledge, 2013, pp. 278–286.

Program by section

Program by section

College Composition and Communication is published exclusively for professors of college composition at two- and four-year institutions.

College Composition and Communication is published exclusively for professors of college composition at two- and four-year institutions.