Conference on College Composition and Communication

September 2020

Background Information

Read this message from Vershawn Ashanti Young, CCCC Chair, and Temptaous McKoy, Chair, CCCC Black Technical and Professional Writing Task Force, about the development of and exigency for this statement.

CCCC Black Technical and Professional Writing Task Force

Temptaous Mckoy, Chair, Bowie State University

Cecilia D. Shelton, University of Maryland

Donnie Sackey, University of Texas at Austin

Natasha N. Jones, Michigan State University

Constance Haywood, Michigan State University

Ja’La Wourman, Michigan State University

Kimberly C. Harper, North Carolina A&T State University

As a coalition of Black scholars, we participated in the Black Technical and Professional Writing Task Force convened by CCCC chair Vershawn Ashanti Young to create a position statement regarding Black technical and professional communication. In addition to fulfilling that charge, we used our agency as scholars in the area to produce the resource list presented here. We composed this position statement and resource list as initial steps toward defining Black technical and professional communication practices and practitioners; advocating for their inclusion in the body of mainstream disciplinary literature; and carving out the methodological, theoretical, and practical space that will enable other Black scholars in the field to see and do such work. The statement and resource list will also assist teachers and researchers of technical and professional communication.

Black technical and professional communication (TPC) is defined as including practices centered on Black community and culture and on rhetorical practices inherent in Black lived experience. Black TPC reflects the cultural, economic, social, and political experiences of Black people across the Diaspora. It also includes the work of scholars in the academy and the contributions of practitioners. In all, Black TPC contextualizes the experiences and cultures of Black peoples through research, teaching, and scholarship.

In lieu of a traditional written statement, we offer a thematically organized and contextualized list of suggested readings drawn from both within and outside of the discipline and the academy. We believe that these resources will begin defining the contours of the scholarship, activism, and design work that Black technical communicators and scholars are (and have been) doing. Furthermore, we believe that offering this resource, rather than a traditional statement, will help scholars better equip themselves with access to appropriate readings to continue the work of Black technical and professional communication advocacy.

Engaging with the Resources Provided

This resource list represents the beginnings of scholarship examining the Black experience in technical and professional communication. Achieving inclusion in TPC and in the academy requires scholarship that examines efforts to create a more equitable, socially just, and race-conscious academic field. The resources presented here include research addressing issues of inclusion and equity as related to Black scholars; this list is not exhaustive.

We identify three goals for this resource list:

- To advocate for the inclusion of Black TPC scholars’ intellectual contributions, acknowledging that our scholarship and rhetorical traditions are fundamental to developing a fuller and richer understanding of TPC’s disciplinary history and future

- To raise awareness of and amplify Black TPC methodologies, theoretical frameworks, and spaces and places of practice

- To identify the contours of scholarly, activist, and design work in which Black TPC practitioners have long been and continue to be engaged

As you engage with this list, please be aware that some resources are repeated across categories because we acknowledge the overlap in ideas and primary concepts. As a coalition of scholars, we are working actively to amplify Black scholars and scholarship in TPC. With that in mind, please look forward to the publication of an already-in-progress article detailing the contemporary trajectory of Black research and pedagogy in our field. The following list summarizes the themes addressed here.

Black User Experience Design: Our attention to Black perspectives on user experience design answers the question of how we can use design to enable more inclusive experiences across users, especially for Black people.

In the Community: We draw your attention to community through literature on space and place in order to consider how Blackness constitutes and is constituted by location.

Black Rhetorics of Health Communication: We draw your attention to the importance of understanding rhetorics of health communication from a Black perspective.

Social Movements, Black Activism, and Digital Rhetorics: We draw your attention to the long-standing themes of social justice in the Black rhetorical tradition and the tactics that activists use to advance social movements.

Black Cultural Rhetorics as Technical and Professional Communication: We draw your attention to the presence of Black culture and its influence on the production of technical and professional communication.

Black Digital Methods and Methodologies: We draw your attention to conversations and developing methodologies across a number of fields that use Black experience and existence as a place of departure.

Narrative and Black Experiences in TPC and the Academy: We draw your attention to the labor bestowed upon and endured by Black scholars in sharing their narratives alongside and within their TPC scholarship.

Black User Experience Design

User experience design from the perspective of Black TPC taps into Molefi K. Asante’s concept of Afrocentricity by placing the suppressed histories and experiences of the Black Diaspora at the center of evaluating the social, economic, and political aspects of design. These perspectives are driven by practitioners (rather than scholars) of technical and professional communication who push against the marginalization of Black lived experiences in design thinking. Their perspectives encourage us to consider design as it positively impacts and emerges from the needs of the Black community.

“Benjamin Evans: The Power of Inclusive Design.” Design Better from InVision, 28 May 2019, https://www.designbetter.co/podcast/benjamin-evans.

Blacks Who Design. Blacks Who Design, 2020, https://blackswho.design.

Cherry, Maurice, editor. Recognize (design anthology). 30 Sept. 2019, https://www.invisionapp.com/inside-design/category/recognize/.

Gebru, Timnit. “Understanding the Limits of AI: When Algorithms Fail.” MIT Technology Review, 26 Mar. 2018, https://events.technologyreview.com/video/watch/timnit-gebru-ai-limits-algorithms-fail/.

Iyamah, Jacquelyn. “Black People Have Always Been UX Designers: Space-Making Is an

Iterative Design Process.” Medium, 8 June 2019,

https://medium.com/black-ux-collective/black-people-have-always-been-ux-designers-sp

ace-making-is-an-iterative-design-process-fcefe4cce846.

Nechole, Amber. “A Journey into Afrocentric UX.” Medium, 2 Sept. 2018, https://medium.com/black-ux-collective/a-journey-into-afrocentric-ux-2709a3534521.

Revision Path. Maurice Cherry, 28 Feb. 2013, https://revisionpath.com/.

28 Black Designers. 28 Days of Black Designers Project, 2020, www.28blacks.com.

In the Community

Community in Black technical and professional communication involves considering how Black peoples are bound together in place on account of where they live, work, visit, and play. The focus on community in Black TPC centers on considerations of how rhetorical practices construct and are constructed by place to support the lives of Black peoples. In these contexts, communities can be form in workplaces, public spaces (e.g., neighborhoods, towns, barbershops, music venues), private spaces (e.g., churches), and digital spaces (e.g., Black Twitter). A focus on community takes into account the ways in which Black peoples practice forming spaces into places while using these locations to examine identities, experiences, and associations.

Battle-Baptiste, Whitney, and Britt Rusert, editors. W.E.B. DuBois’s Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America. Princeton Architectural Press, 2018.

Brock, André, Jr. Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures. New York UP, 2020.

Byrd, Antonio. “Between Learning and Opportunity: A Study of African American Coders’ Networks of Support.” Literacy in Composition Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2019, pp. 31–55.

———. “‘Like Coming Home’: African Americans Tinkering and Playing toward a Computer Code Bootcamp.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 71, no. 3, 2020, pp. 426–52.

Finney, Carolyn. Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors. U of North Carolina P, 2014.

Florini, Sarah. Beyond Hashtags: Racial Politics and Black Digital Networks. New York UP, 2019.

McIlwain, Charlton D. Black Software: The Internet and Racial Justice, from the AfroNet to Black Lives Matter. Oxford UP, 2019.

Moore, Kristen R. “Black Feminist Epistemology as a Framework for Community-Based Teaching.” Key Theoretical Frameworks: Teaching Technical Communication in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Angela M. Haas and Michelle F. Eble, Utah State UP, 2018, pp. 185–211.

Moss, Beverly J. A Community Text Arises: A Literate Text and a Literacy Tradition in African-American Churches. Hampton Press, 2003.

Black Rhetorics of Health Communication

Black rhetorics of health communication (BRHC) build on the work of scholars from health communication, rhetorics of health and medicine, technical and professional communication, medical communication, rhetoric, and other fields. BRHC scholarship acknowledges the health disparities and generational mistrust that Black communities have in relation to the medical establishment and discusses what happens when race, gender, and class intersect with the health-care industry. It takes account of Black maternal health, reproductive justice, Black feminism, and rhetorical theories. It brings together academics, practitioners, and health-care providers from divergent fields to discuss the design, delivery, and effects of written documents on patients, communities, and the medical profession. These works, while not rooted in TPC, are integral to any study of health communication that aims to understand and deal with issues of ethics and health disparities in American medical culture.

Davis, Angela. “Racism, Birth Control, and Reproductive Rights.” Women, Race, and Class. Random House, 1983, pp. 202–21.

Harper, Kimberly C. The Ethos of Black Motherhood in America: Only White Women Get Pregnant. Lexington Books, 2020 (forthcoming).

Heifferon, Barbara, and Stuart C. Brown. Rhetoric of Healthcare: Essays toward a New Disciplinary Inquiry. Hampton Press, 2008.

Jones, James H. Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. Free Press, 1993.

Nelson, Alondra. Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight against Medical Discrimination. U of Minnesota P, 2013.

Roberts, Dorothy. Killing the Black Body: Race Reproduction and the Meaning of Liberty. Vintage, 1999.

Ross, Loretta J. The Color of Choice: White Supremacy and Reproductive Justice. Duke UP, 2016.

Ross, Loretta J., and Rickie Solinger. Reproductive Justice: An Introduction. U of California P, 2017.

Smith, Wilbert. Hole in the Head: A Life Revealed. Christian Faith, 2018.

Townes, Emilie M. Breaking the Fine Rain of Death: African American Health Issues and a Womanist Ethic of Care. Wipf and Stock, 1998.

Washington, Harriet A. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. Harlem Moon, 2006.

Social Movements, Black Activism, and Digital Rhetorics

With the social justice turn in TPC studies (see, for instance, Technical Communication After the Social Justice Turn: Building Coalitions for Action, Rebecca Walton et al., Routledge, 2019), much more scholarly and pedagogical focus has been applied to the ways in which technical and professional communication reinscribe inequities, as well as the possibilities for our discipline to intervene toward more just outcomes. As one might expect, this focus includes both a growing body of research on racial justice and calls for the fields of technical communication and professional communication to specifically redress racial harm. The short bibliography presented here aims to add dimensions to that call in three ways: (1) focusing on technology and anti-Blackness, (2) focusing on Black activists’ and Black researchers’ communication and analysis of technology and Blackness, and (3) focusing on Black activist rhetorics as kinds of technical communication.

Benjamin, Ruha. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Polity Press, 2019.

Black Lives Matter. https://blacklivesmatter.com/. Accessed 8 Aug. 2020.

BYP100. Black Youth Project 100. https://www.byp100.org/. Accessed 8 Aug. 2020.

Browne, Simone. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Duke UP, 2015.

Heyl, Julia Childs. “We Hid Escape Routes in Our Roots: Honoring the History of Hair Braiding in the Black Community.” Julia Childs Heyl, 25 July 2019, http://juliachildsheyl.com/we-hid-escape-routes-in-our-roots-honoring-the-history-of-hair-braiding-in-the-black-community/.

Jones, Natasha N. “The Importance of Ethnographic Research in Activist Networks.” Communicating Race, Ethnicity, and Identity in Technical Communication, edited by Miriam F. Williams and Octavio Pimentel, Taylor & Francis, 2014, pp. 46–61.

Shelton, Cecilia D. On Edge: A Techné of Marginality. 2019. East Carolina University, PhD dissertation. http://hdl.handle.net/10342/7433.

Black Cultural Rhetorics as Technical and Professional Communication

Cultural rhetorics in TPC call for the use of nontraditional knowledge-making practices that are not directly tied to institutional or higher-education knowledge. Moreover, cultural rhetorics in TPC combine the lived experiences of practitioners with what we’ve come to know, and even redefine, TPC to be. This list includes scholarship that exemplifies the combination of culture and the academy while remaining true to the origin of information and its relevance.

Banks, Adam J. Race, Rhetoric, and Technology: Searching for Higher Ground. Routledge, 2006.

Carson, A. D. Owning My Masters: The Rhetorics of Rhymes & Revolutions. 2017. Clemson University, PhD dissertation.

Cobos, C., et al. “Interfacing Cultural Rhetorics: A History and a Call.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 37, no. 2, 2018, pp. 139–54.

Hierro, Victor Del. “DJs, Playlists, and Community: Imagining Communication Design through Hip Hop.” Communication Design Quarterly Review, vol. 7, no. 2, 2019, pp. 28–39.

Jackson, Ronald L., II, and Elaine B. Richardson, editors. Understanding African American Rhetoric: Classical Origins to Contemporary Innovations. Routledge, 2014.

Leger, Shewonda. The Cultivation of Haitian Women’s Sense of Selves: Towards a Field of Action. 2019. Michigan State University, PhD dissertation.

Mckoy, Temptaous T. Y’all Call It Technical and Professional Communication, We Call It #ForTheCulture: The Use of Amplification Rhetorics in Black Communities and Their Implications for Technical and Professional Communication Studies. 2019. East Carolina University, PhD dissertation.

Richardson, Elaine. African American Literacies. Psychology Press, 2003.

Watts, Eric King. “‘Voice’ and ‘Voicelessness’ in Rhetorical Studies.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 87, no. 2, 2001, pp. 179–96.

Black Digital Methods and Methodologies

The following is a working list of sources that highlight Black digital methods and methodologies across various fields. One commonality among these methods lies in the fact that they center Black experience(s) as a way of understanding technology, community, ownership, and ethics through a cultural lens. Understanding that digital or online data are “always already” shaped by and through people, these methods stress that data are never separate from human experience. Thus, they remind us that we should continue to cultivate research practices that are critical, relative, and multifaceted.

Brown, Nicole M. “Methodological Cyborg as Black Feminist Technology: Constructing the Social Self Using Computational Digital Autoethnography and Social Media.” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, vol. 19, no. 1, 2019, pp. 55–67.

Everett, Anna. “The Revolution Will Be Digitized: Afrocentricity and the Digital Public Sphere.” Social Text, vol. 20, no. 2, 2002, pp. 125–46.

Jones, Natasha N. “Rhetorical Narratives of Black Entrepreneurs: The Business of Race, Agency, and Cultural Empowerment.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication, vol. 31, no. 3, 2017, pp. 319–49.

Richardson, Elaine, and Alice Ragland. “#StayWoke: The Language and Literacies of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement.” Community Literacy Journal, vol. 12, no. 2, 2018, pp. 27–56.

Sawyer, LaToya Lydia. “Don’t Try and Play Me Out!”: The Performances and Possibilities of Digital Black Womanhood. 2017. Syracuse University, PhD dissertation. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/785.

Wourman, Ja’La J., and Shingi Mavima. “Our Story Had to Be Told! A Look at the Intersection of the Black Campus Movement and Black Digital Media.” Spark: A 4C4Equality Journal, vol 2, no. 9, 2020, sparkactivism.com/volume-2-call/vol-2-intro/our-story-had-to-be-told/.

Narrative and Black Experiences in TPC and the Academy

The following list provides resources on narrative (and storytelling) and Black experiences in TPC and the academy. Narrative resources can include scholarship that examines or explains how narrative, storytelling, or both are used by Black scholars (in method, theory, and practice). Narrative approaches to research and pedagogy often highlight the lived experiences of Black scholars in TPC, in the academy, and in the world. As a result, this list also includes scholarship about the lived experiences of Black scholars in technical and professional communication and beyond.

Baker-Bell, April. “For Loretta: A Black Woman Literacy Scholar’s Journey to Prioritizing Self-Preservation and Black Feminist–Womanist Storytelling.” Journal of Literacy Research, vol. 49, no. 4, 2017, pp. 526–43.

Edwards, Jessica. “Race and the Workplace: Toward a Critically Conscious Pedagogy.” Key Theoretical Frameworks: Teaching Technical Communication in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Angela M. Hass and Michelle F. Eble, Utah State UP, 2018, pp. 268–86.

Jones, Natasha N. “Narrative Inquiry in Human-Centered Design: Examining Silence and Voice to Promote Social Justice in Design Scenarios.” Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, vol. 46, no. 4, 2016, pp. 471–92.

Jones, Natasha N., and Miriam F. Williams. “Technologies of Disenfranchisement: Literacy Tests and Black Voters in the US from 1890 to 1965.” Technical Communication, vol. 65, no. 4, 2018, pp. 371–86.

Mckoy, Temptaous T. Y’all Call It Technical and Professional Communication, We Call It #ForTheCulture: The Use of Amplification Rhetorics in Black Communities and Their Implications for Technical and Professional Communication Studies. 2019. East Carolina University, PhD dissertation.

Williams, Miriam F. From Black Codes to Recodification: Removing the Veil from Regulatory Writing. Routledge, 2017.

———. “A Survey of Emerging Research: Debunking the Fallacy of Colorblind Technical Communication.” Programmatic Perspectives, vol. 5, no. 1, 2012, pp. 86–93.

———. “Tracing WEB Dubois’ ‘Color Line’ in Government Regulations.” Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, vol. 36, no. 2, 2006, pp. 141–65.

Williams, Miriam F., and Octavio Pimentel. Communicating Race, Ethnicity, and Identity in Technical Communication. Routledge, 2016.

This position statement may be printed, copied, and disseminated without permission from NCTE.

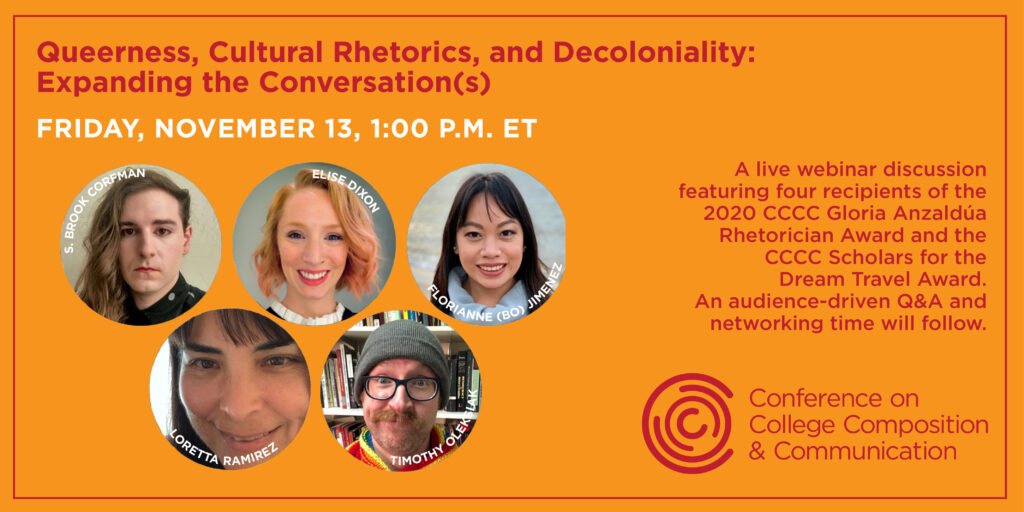

S. Brook Corfman, University of Pittsburgh

S. Brook Corfman, University of Pittsburgh Elise Dixon, University of North Carolina at Pembroke

Elise Dixon, University of North Carolina at Pembroke Florianne (Bo) Jimenez, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Florianne (Bo) Jimenez, University of Massachusetts Amherst Loretta Ramirez, California State University, Long Beach

Loretta Ramirez, California State University, Long Beach Timothy Oleksiak, University of Massachusetts Boston

Timothy Oleksiak, University of Massachusetts Boston Jackie Rhodes, Michigan State University

Jackie Rhodes, Michigan State University